The timing of operating improvements across the investment lifecycle

Over the past ten years, private equity firms have increasingly recognized the contribution of operational improvements to the overall value creation efforts at underlying portfolio companies. As a result, we have witnessed a dramatic evolution in the operating focus of private equity firms and the resources that they are committing to this initiative and investment. While many firms are still maturing their investment models to support this new reality, others have expanded their capabilities both in how they drive operational improvements and, more interestingly, when they are most effectively able to pull these value levers.

The value of operational improvements

As the private equity industry has matured, the sheer number of firms competing for a finite universe of investment opportunities has resulted in a new dynamic emerging. Firms need to employ more tools than financial engineering, thereby increasing the importance of operational enhancements.

Maine Pointe, a leading operational implementation consulting firm, conducted a survey of 50 private equity firms and asked them about the deployment of operating models and the value they were gaining from those investments. Findings from the survey reinforce the importance of operating capability:

- 75% of US respondents (53% in Europe) currently deploy some form of operating partner model.

Of those firms:

– Over 90% also utilize outside operational expertise to drive value creation projects

– 72% claim that this has resulted in significant operating improvements, contributing to the exit valuation nearly 60% of the time - Over 50% of the firms attributed more than 50% of the total value creation strategy to operational improvements.1

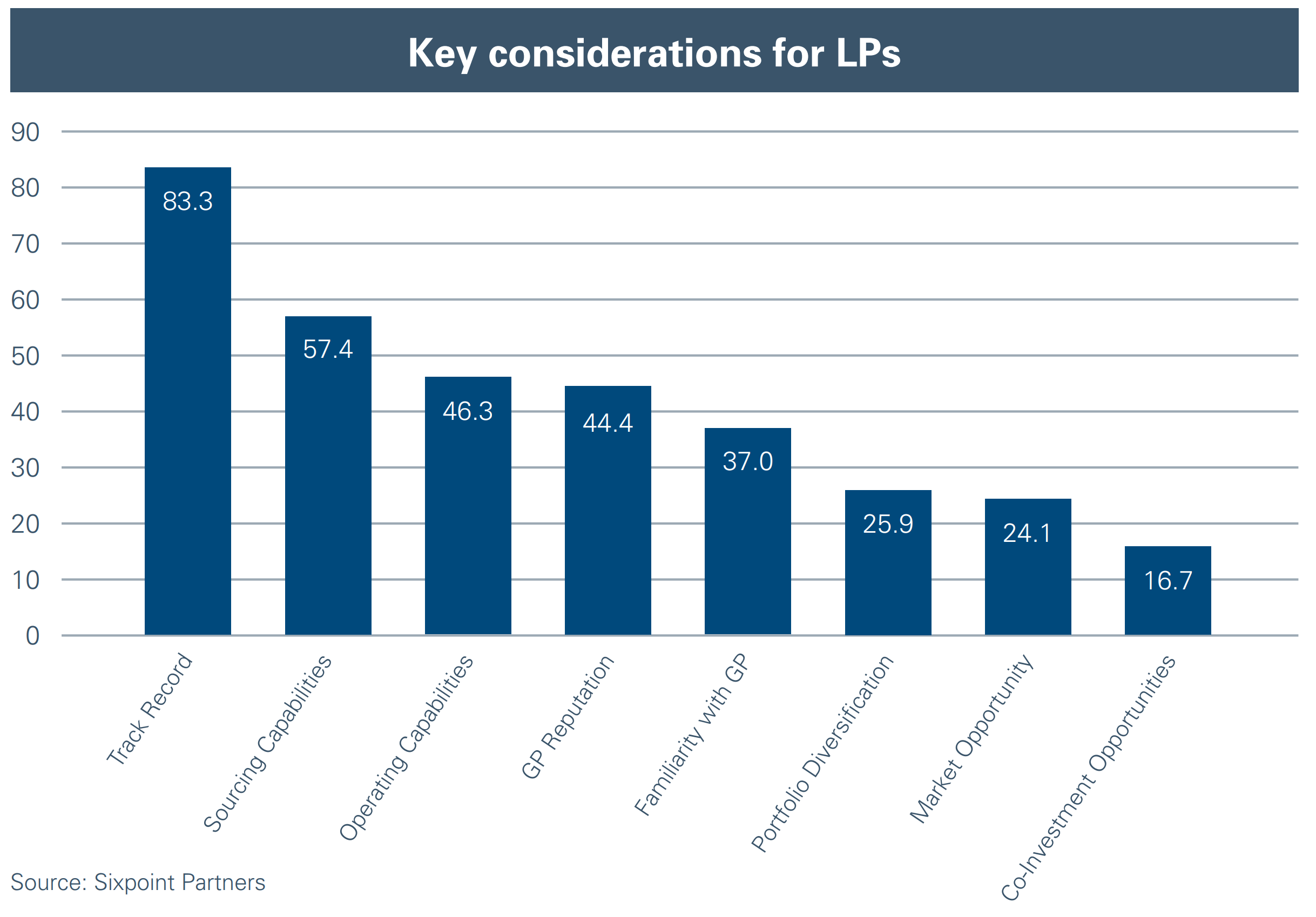

The importance of operating improvements across the buy-make-move-fulfill supply chain has not escaped the attention of LPs, who increasingly view operating capability as a key differentiator in their evaluation of GPs with whom to partner. Maine Pointe’s survey of private equity operating partners1 found that over 70% see an increasing level of interest from potential acquirers in their firm’s operating capabilities.

The survey also highlights the wide variety of operating models, often based on the size of the private equity firm, with only 35% having in-house operating resources in addition to an operating partner.

In a recent Sixpoint Partners survey of 76 LPs, the respondents placed a greater significance on “Operating Capabilities” than the “GP Reputation,” or even their “Familiarity with the GP”.

Those in-house resources can grow to become large operating teams, often with functional specialization such as procurement, human capital and cost cutting. Individual operating partners can take on many different roles, from a one-to-one association with specific portfolio companies, to a one-to-all association covering the entire portfolio.

Timing has many drivers

With operating improvements firmly ensconced in the minds of all stakeholders, and many settling on the operating model that works for them, the question becomes: when is the right time to make operating changes?

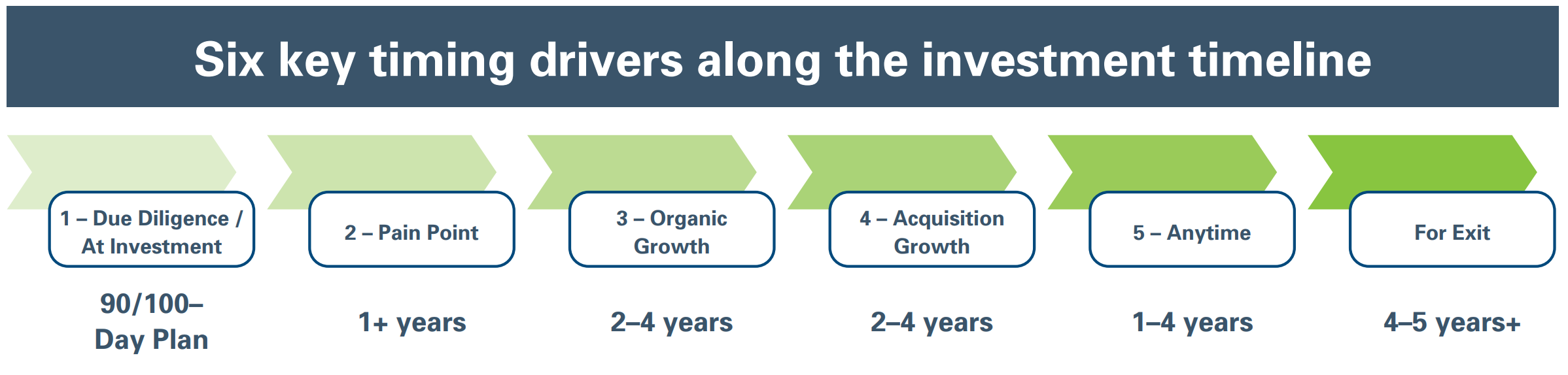

Let’s explore 6 key timing drivers where circumstances drive the potential for operating value creation.

Six key timing drivers to maximize value

Time Driver 1: Due Diligence and At-Investment

Implementing changes immediately upon close, based on the value creation plan developed during due diligence with management teams, represents a common and obvious point of intervention. This can be solely conducted by the management team, supported by the operating model of the GP, or done utilizing outside resources.

Time Driver 2: Pain Point

It is common for businesses to go into a regular monitoring mode and for operating focus not to re-engage until there is a continuing pain point. Once operating performance reaches the threshold where both parties acknowledge that normal management efforts are not working, targeted interventions are taken.

Time Driver 3: Organic Growth

Whether through market growth, customer or geographic expansion, or market share increase, organic growth often takes companies to the next level of revenue or complexity, requiring additional sophistication to run the business successfully. In each major step of growth, a significant change is required in operating practices. These changes are required not only to reap the financial rewards of scale, but also to maintain consistent quality, service and productivity to sustain or improve the company’s performance.

Time Driver 4: Acquisition/Add-On Growth

This driver takes the needs described in time driver 3 and adds the complexity of it being caused by both organic growth and that of acquisitions or add-ons. The need to mature the company’s capabilities, organizational structure and processes is now complicated by the existence of multiple operating structures, potentially mediocre integrations, competing/conflicting processes and disparate system complexities.

Frequently the first few add-ons are absorbed without difficulty but, as those add up over time, a tangled web can develop in the operating of the company that must be undone to unlock value and create a viable operation for eventual exit. This driver may occur at any point but very often drives change in the 12 months prior to exit to facilitate maximum value. In 2011, the Cass Business School in London added to the body of research that supports the case that, in reality, many acquisitions do not deliver significant long-term value.

Their analysis of UK M&A activity2 found that successful firms are in the minority, while most companies fail to realize operational improvements and actually see a decrease in profitability within 3 years of an acquisition.

Time Driver 5: More Value Anytime

An often-overlooked intervention point is the operating analysis that occurs when there is no pain point and no obvious crisis that has been created by growth.

The reason for making the investment of time, money and focus is because there are always opportunities to improve operations and synergies across the buy-move-make-fulfill supply chain. For this point, an outside perspective is almost a necessity in order to take a fresh view of the operation.

Time Driver 6: Prepare for Sale

For any investment that firms are looking to exit in the next 12-18 months, it makes sense to conduct a full external review of all the operating areas to identify any potential opportunities that have been missed and make targeted change to capture that last segment of value. There is a greater need for specialist external assistance in conducting the review and implementation of change at this point.

This is because many internal biases have been in place for a long period of time and acceleration is needed to make changes in time for exit valuation. This particular time driver could assist in identifying opportunities as a result of any of the previous situations

(remnants of the original investment strategy, organic or acquisition growth, pain points or newlyidentified opportunities).

Real-world insight into externally driven operating improvements

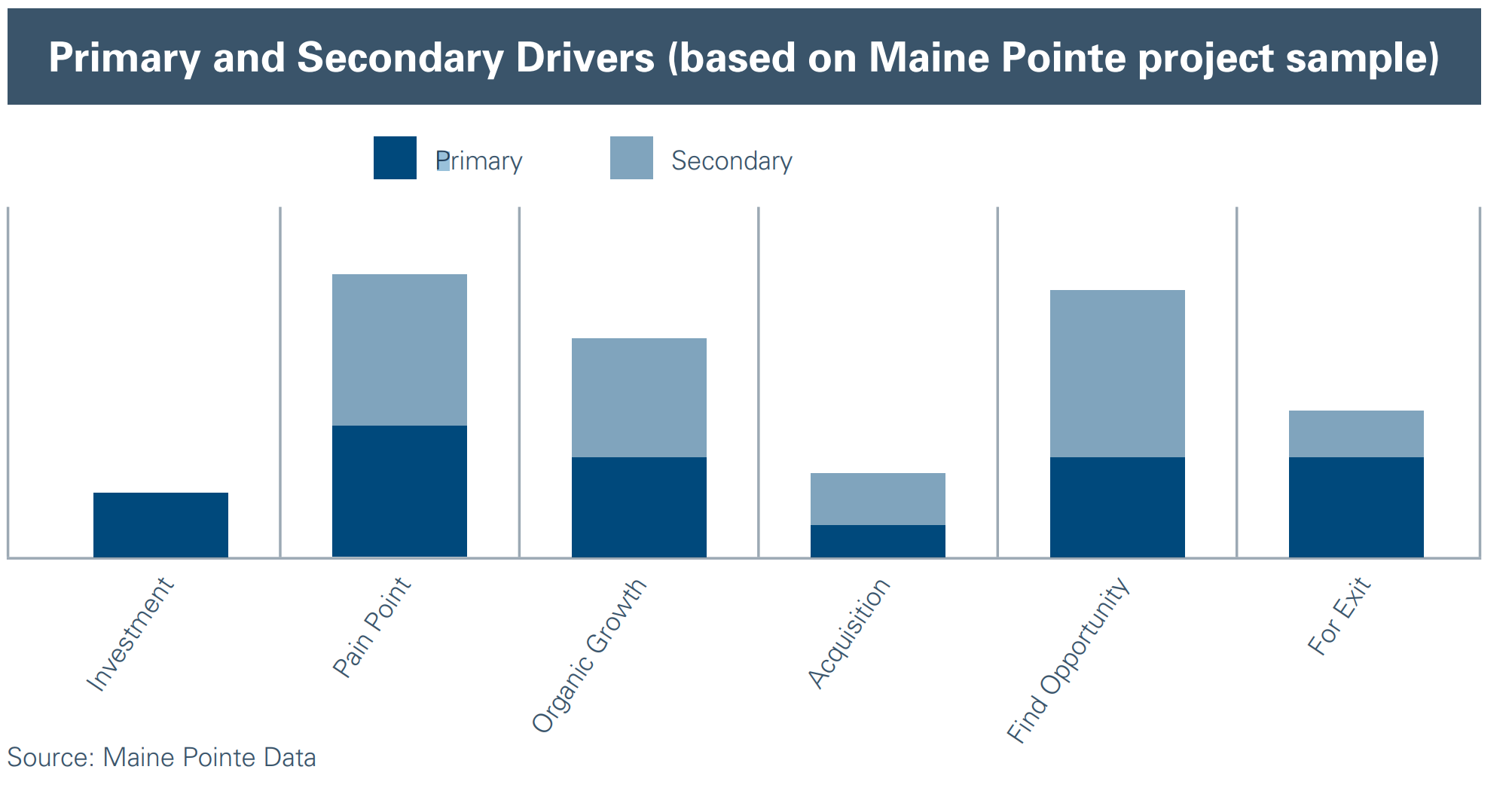

Based on the definition of the six time drivers for making significant operating improvements, Maine Pointe analyzed a sample of 40 projects conducted on behalf of private equity firms and their portfolio companies to understand which drivers were most prevalent at the time, when in the investment lifecycle those drivers initiated engagements, and what the typical results looked like.

1. Primary & secondary drivers across the Investment Timeline

Findings: Any of the timing drivers are viable entry points for external assistance. Pain points, or a desire to find opportunities across the company, are the most common. The amount of interventions preparing for exit is significant and has been trending higher as valuations remain high.

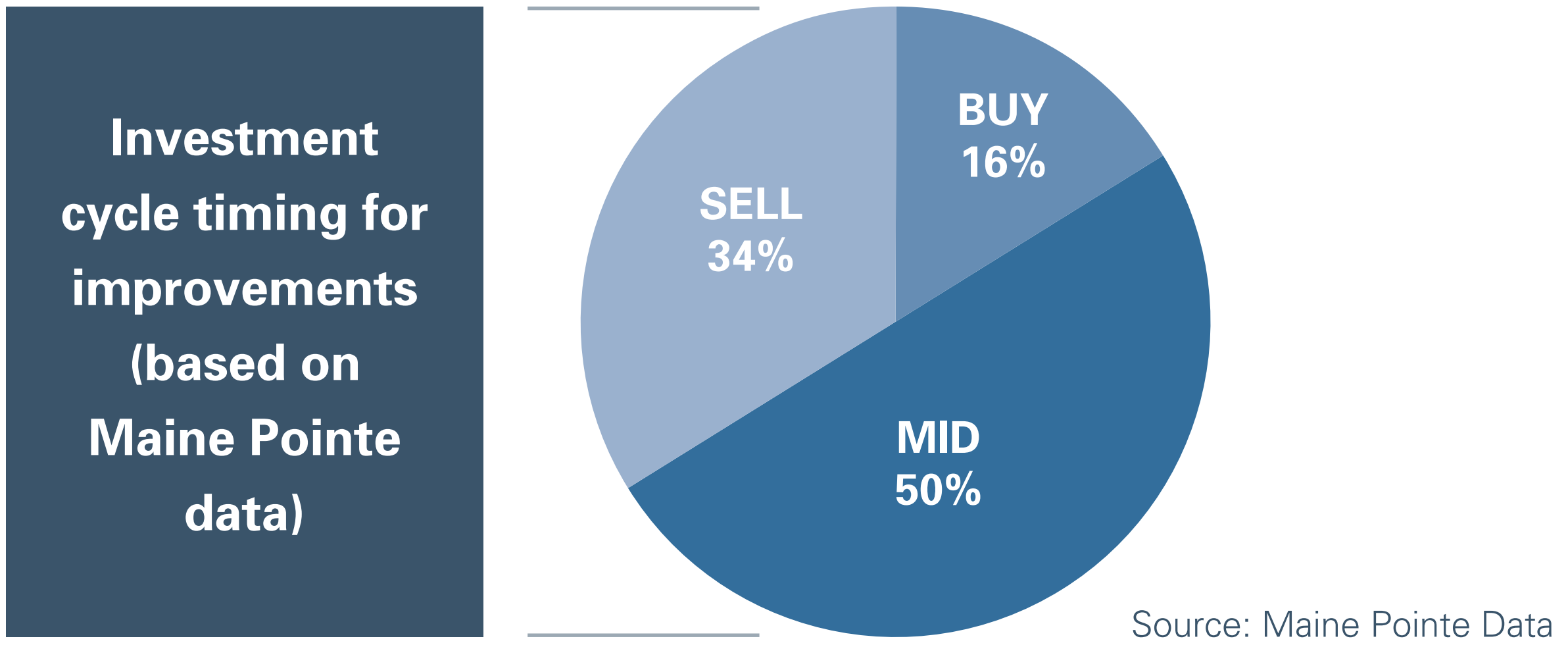

2. Investment cycle timing for improvements across the investment timeline

Findings: Over a third of the time, external resources are being brought in to assist 12-18 months prior to sale, after acquisitions, add-ons, or growth have created a final opportunity to capture EBITDA.

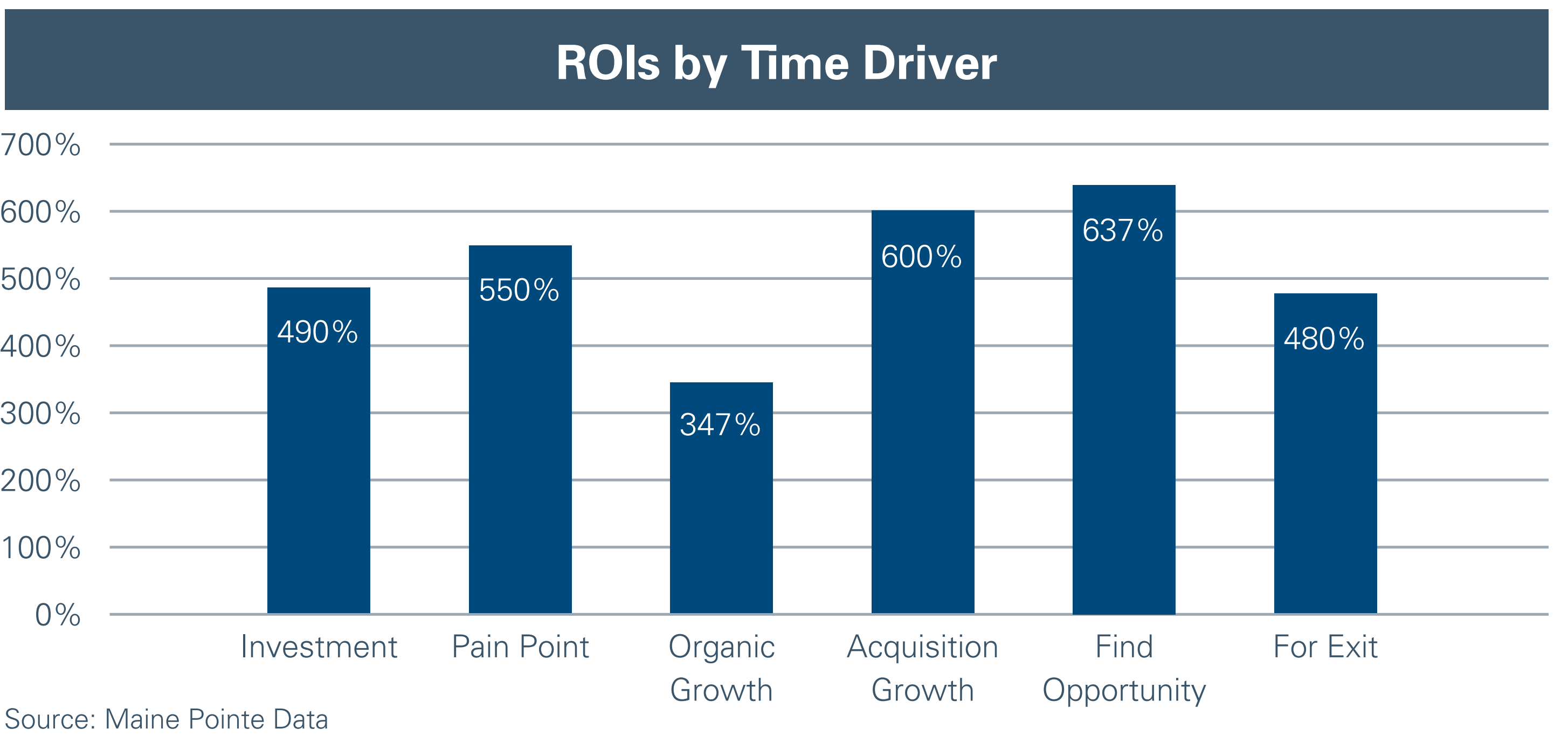

3. Primary driver ROI across the Investment Timeline

Findings: There are solid returns for external assistance at any point, with the average ranging from 3.5:1 to 6:1, although individual engagement returns can be much higher. The highest return is when external resources have full license to search for all opportunities across the buy-make-move-fulfill supply chain – what Maine Pointe calls Total Value Optimization™.

“Total Value Optimization™ (TVO) is achieved when an organization is dynamically able to anticipate and meet demand through the synchronization of its buy-make-move-fulfill supply chain to deliver the greatest value to customers and investors at the lowest cost to business.”

Three success story examples across the investment cycle

This section outlines three case study examples where operational improvement projects were initiated and supported by the Maine Pointe consulting team at various points in the investment lifecycle.

Case Study 1

Time Driver 1: Diligence and Initial Investment

The supply chain as a strategic driver for cost and growth

Company description: A middle-market industrial player in the resins market.

Issue/problem: There was substantial urgency driven from poor profitability and a recent bankruptcy. Suppliers perceived the company as high risk and many refused to do business with them or, if they would, required payment up front. Meanwhile competition was stealing market share at lower costs, befuddling the company who had thought there were no other lower cost

supply sources.

Solution: As part of the due diligence process conducted on behalf of the two co-investing private equity firms, Maine Pointe extensively reviewed the data room and applied the data against key benchmarks. Maine Pointe was able to identify the potential for some significant savings. As the transaction was completed, a CEO transition took place and alignment with the management team was the first crucial driver of success, particularly at the beginning of the investment.

In examining the overall value creation plan, the opportunity to improve the supply chain had the lowest risk and greatest potential reward, so the project was initiated. The first step was to educate the company about the alternative low-cost sources in the global market.

In parallel, the company worked to develop unique competitive advantages with alternative resin formulations. Using the Maine Pointe 6-Step Strategic Sourcing Process, the team created ‘quick wins’, through immediate supply alternatives and incumbent cost reductions, in the United States, then Canada, then the Middle East and Europe, and finally in South America. Supplier forums and CEO road shows were used to change perceptions and attitudes of the supply base. RFPs and negotiations followed as part of other strategic sourcing activities that ended up producing an overall cost reduction of 4% on top of plunging market prices.

Results: The company was able to compete in the market place based on new products and lower costs. The supply chain was reliable and they had reinvigorated their relationships with their vendor partners. The PE firms now had an investment with dramatic EBITDA improvements and market growth that eventually paved the way to an extremely profitable, and probably more rapid, exit. The return-on -investment during the first year alone from using outside resources was 5:1.

Key takeaway: Based on this example, it’s critical to get a true operational review conducted during the diligence phase or immediately upon investment to identify potential opportunities. The sooner those actions can be implemented, the faster those results can strongly position the company both in terms of profitability and growth.

Case Study 2

Time Driver 4: Growth Through Add-ons

Cleaning up many add-ons

Company description: Middle-market, highly -diversified industrial company.

Issue/problem: In recent years, many private equity investments have had a strategy that relies heavily on industry consolidation through extensive add-on acquisitions. The idea is to not only build the company’s product depth and breadth, but also to capture the increased multiples associated with a larger firm.

Solution: Maine Pointe helped to bring together the structure, processes, and value from a company that had done over 100 add-on acquisitions in its history. It was an obvious play to focus on strategic procurement and bring together the mix of companies that had few purchasing controls, a huge variety of specifications, and an out-of-control scheme of managing the supply chain.

The analysis process was particularly difficult in this situation due to the number of disparate systems and proliferation of SKUs, with ten new SKUs being generated every day. Less than 20% of the procurement spend was under contract, logistics costs were escalating, and there were over 100 brokers and intermediaries being used.

Results: Although the magnitude of add-ons may be the extreme, dealing with their integration is a common situation where the typical results are projected at a 4:1 return-on-investment, as in this example.

Key takeaway: The value-creation return natural to the add-on strategy can be multiplied by formally going through an integration and supply chain optimization improvement effort with the new entity. It delivers additional EBITDA and creates a sustainable organization going forward, which is critical to future investors.

Case Study 3

Time Driver 5: Is There Opportunity?

Combine operations and procurement improvement to drive enhanced value

Company description: Major flexible packaging company with operations on five continents. It

was a steady revenue business but there was little room for growth from the main product.

Issue/problem: The Company was facing a significant challenge relating to their metrics and management operations at their two main facilities. They had sunk $6M into an ERP implementation that had delivered little value. There was a sense that there was a significant

dollar and performance opportunity in the company’s operations and procurement functions, but how to capture it?

Solution: Maine Pointe’s integrated approach focused simultaneously on procurement and operations to break down silos and deliver value across business functions. Our approach aligned supply chain and materials strategies with operational strategies resulting in increased accuracy of information and more-informed decision making. The company was able to rapidly drive out performance improvements with a 3.3:1 ROI.

Key takeaway: There is considerable power in implementing operational improvements throughout the investment cycle - not only to react to a major pain point -but to “see what opportunities exist”. Not only can it deliver substantial value, but it can be the enabler to execute the growth-side strategies of the business.

What does it mean?

With all stakeholders placing an increasing value on operating improvements, private equity firms must look towards all the variables in how they operate and provide value creation support. These options include a variety of operating models, the selection of internal approaches or external implementation partners, and the timing-triggers for taking action.

The timing-triggers analysis shows that all six points are viable considerations for a call-to-action, with good ROIs across the board when external resources are used. Some of the most common historical intervention points, such as the initial 90-day plan, are matched, or exceeded, by some of the least common intervention points. For example, conducting an external review after years of investment without an identified pain point.

As private equity investment leadership and operating partners examine their investment portfolio, this model may provide a different way of considering when major interventions may produce value.

Sources:

1. The snapshot survey was conducted online and through confidential, direct conversations with 50 Private Equity executives across the United States and Europe during April and May 2015. The executives represented a wide variety of industry sectors and companies ranging in size from small to large, with an average of $11B in assets.

2. The Economic Impact of M&A: Implications for UK firms, M&A Research Centre, Cass Business School, 2011